A UC Riverside-led team has created a chemical to help plants hold onto water, which could stem the tide of massive annual crop losses from drought and help farmers grow food despite a changing climate.

“Drought is the No. 1 cause, closely tied with flooding, of annual crop failures worldwide,” said Sean Cutler, a plant cell biology professor at UC Riverside, who led the research. “This chemical is an exciting new tool that could help farmers better manage crop performance when water levels are low.”

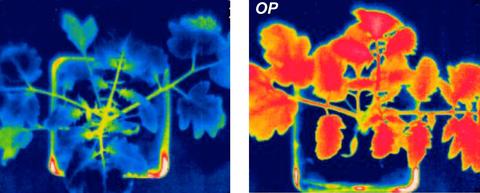

Details of the team's work on the newer, more effective anti-water-loss chemical is described in a paper published today in Science. This chemical, Opabactin, is also known as “OP,” which is gamer slang for “overpowered,” referring to the best character or weapon in a game.

“The name is also a shoutout to my 10-year-old at home,” Cutler said.

An earlier version of OP developed by Cutler's team in 2013, called Quinabactin, was the first of its kind. It mimics abscisic acid, or ABA, the natural hormone produced by plants in response to drought stress. ABA slows a plant's growth, so it doesn't consume more water than is available and doesn't wilt.

“Scientists have known for a long time that spraying plants with ABA can improve their drought tolerance,” Cutler said. “However, it is too unstable and expensive to be useful to most farmers.”

Quinabactin seemed to be a viable substitute for the natural hormone ABA, and companies have used it as the basis of much additional research, filing more than a dozen patents based on it. However, Quinabactin did not work well for some important plants, such as wheat, the world's most widely grown staple crop.

When ABA binds to a hormone receptor molecule in a plant cell, it forms two tight bonds, like hands grabbing onto handles. Quinabactin only grabs onto one of these handles.

Cutler's team searched millions of different hormone-mimicking molecules that would grab onto both handles. This searching, combined with some chemical engineering, resulted in OP.

OP grabs both handles and is 10-times stronger than ABA, which makes it a “super hormone.” And it works fast. Within hours, Cutler's team found a measurable improvement in the amount of water plants released.

Because OP works so quickly, it could give growers more flexibility around how they deal with drought.

“One thing we can do that plants can't is predict the near future with reasonable accuracy,” Cutler said. “Two weeks out, if we think there's a reasonable chance of drought, we have enough time to make decisions — like applying OP — that can improve crop yields.”

Initial funding for this project was provided by Syngenta, an agrochemical company, and the National Science Foundation.

Members of the research team included others from UCR, the Medical College of Wisconsin, Utah State University, and PRESTO Japan Science and Technology Agency, as well as Shizuoka, Tottori, and Utsunomiya universities in Japan.

Cutler's team is now trying to “nerf” their discovery.

“That's gamer speak for when a weapon's power is reduced,” Cutler said.

Whereas OP slows growth, the team now wants to find a molecule that will accelerate it. Such a molecule could be useful in controlled environments and indoor greenhouses where rainfall isn't as big a factor.

“There's times when you want to speed up growth and times when you want to slow it down,” Cutler said. “Our research is all about managing both of those needs.”