Posts Tagged: mandarin

IPM Insights into What Katydid

The UC IPM Citrus Pest Management Guidelines has been updated to include new research out of the Rosenheim lab at UC Davis. Early-season pests like citrus thrips, earwigs, and katydids damage some types of mandarins differently. Learn how to adjust your management program accordingly. Many new photos have been added to these sections to improve pest identification and show more damage symptoms.

Scarring on the stylar end of citrus fruit caused by citrus thrips, Scirtothrips citri, feeding. Photo credit: Tobias G. Mueller

Adult male European earwig, Forficula auricularia. Photo credit: Beth Grafton-Cardwell.

Scar on citrus fruit caused by European earwig, Forficula auricularia, feeding. Photo credit:Hanna Kahl.

What's Happening with Citrus Production?

The USDA has released their Fruit and Nuts Outlook Report which shows the forecast the 2019/2020 seasons and provides an overview of the markets.

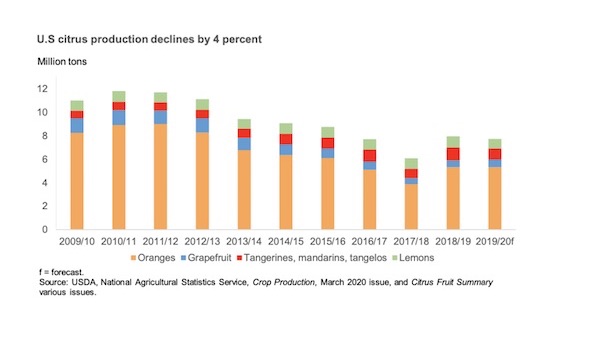

The 2019/20 citrus crop is forecast to be 7.63 million tons, down 4 percent from the previous season. Declines in overall production can mostly be attributed to smaller lemon, tangerine, and mandarin crops in California. Orange production in California has remained stable since last season. Citrus production in Florida has also remained stable with a 1 percent decline in orange production, and significant increases in grapefruit, tangerine, mandarin, and tangelo production over last year. Overall decreases in production of lemons, tangerines, mandarins, and tangelos are expected to result in increased imports, and higher prices compared with last year.

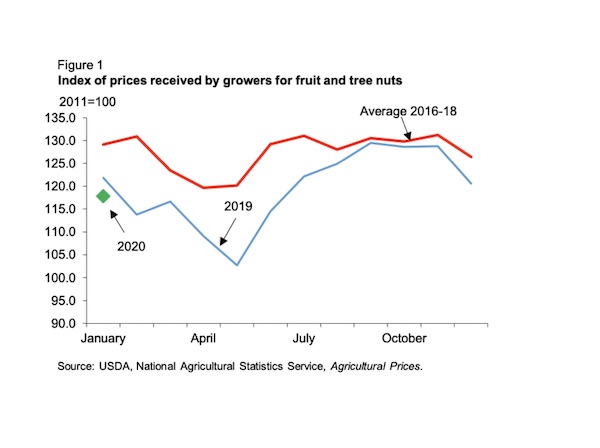

Fruit and tree nut grower prices began 2020 at low levels. At 117.8 (2011=100), the January 2020 index was down 10 percent from the January 2019 index and below the January average for 2016-18 (fig.1). The January 2020 index was the lowest since January 2013. Significantly lower grower prices for citrus fruit and apples drove down the index (table 1).

As of mid-March 2020, U.S. citrus exports were down except for orange juice and tangerines. Reduced exports have increased the domestic supply of citrus, putting downward pressure on prices. The January 2020 price of all- grapefruit is down 36 percent from the year before, and all-oranges and oranges for the fresh market are down by 6.9 and 9.4 percent respectively. All- lemon prices are down 28.5 percent, and fresh lemons prices are down by 8.6 percent.

Apple prices were down 21 percent in January 2020 from the year before. USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) estimates the 2019 total apple crop to be up 3.6 percent from 2018. The strong dollar and increased tariffs in several countries have reduced exports, putting downward pressure on prices.

citrus and mountains

Citrus Splitting

It has been a struggle to get through the summer this year. Weird. Hot. Then fog in August. Hot. Then fog in October. It's supposed to be clear,, blue skies in October. perfect weather for avocado persea mite and citrus leaf miner. Hot times then cooler. How to irrigate? A lot of folks just decided not to irrigate. Why do it when it's so crazy? Forecast was for no rain, but it's cool. And then it rained, and suddenly that beautiful citrus that has just broken color and is an orange globe, splits. It's most common in navels, but all citrus that ripen in the fall – tight-skinned satsuma mandarins, early clementines, tangelos and blood oranges. With the hot summer, it seems that a lot of citrus fruit have accelerated their maturity and are ready, ripe and sweet right now, and maybe ready to split.

And that's the problem. Drought stress. Salt stress due to drought. Water stress due to miserly watering. A heat wave in July. And a weird fall with maybe rain and maybe no rain and is ¼ inch considered rain or just a dedusting? Irregular watering is the key to splitting this time of year. The sugar builds, the pressure to suck in water builds and the fruit has been held back by a constrained water pattern and suddenly some water comes and it goes straight to the fruit and Boom, it splits.

Years of drought, and a stressed tree are a perfect set up for a citrus splitting in fall varieties like navel and satsuma. The days have turned cooler and there's less sense on the part of the irrigator to give the tree water and suddenly out of nowhere, there is rain. That wonderful stuff comes down and all seems right with the world, but then you notice that the mandarin fruit are splitting. Rats? Nope, a dehydrated fruit that has taken on more water than its skin can take in and the fruit splits. This is called an abiotic disorder or disease. However, it's not really a disease, but a problem brought on by environmental conditions. Or poor watering practices.

Fruit that is not yet ripe, like ‘Valencias' and later maturing mandarins are fine because they haven't developed the sugar content and have a firmer skin. They then develop during the rainy season when soil moisture is more regular. Or used to be more regular. With dry, warm winters this may become more or a problem in these later varieties, as well.

Several factors contribute to fruit splitting. Studies indicate that changes in weather, including temperature, relative humidity and wind may exaggerate splitting. The amount of water in the tree changes due to the weather condition, which causes the fruit to shrink. Then with rewetting, the fruit swells and bursts. In the navel orange, it usually occurs at the weakest spot, which is the navel. In other fruit, like blood orange, it can occur as a side split, as seen in the photo below.

Proper irrigation and other cultural practices can help reduce fruit spitting. Maintaining adequate but not excessive soil moisture is very important. A large area of soil around a tree should be watered since roots normally grow somewhat beyond the edge of the canopy. Wet the soil to a depth of at least 2 feet, then allow it to become somewhat dry in the top few inches before irrigating again. Applying a layer of coarse organic mulch under the canopy beginning at least a foot from the trunk can help moderate soil moisture and soil temperature variation.

Once split, the fruit is not going to recover. It's best to get it off the tree so that it doesn't rot and encourage rodents.

(Photo by Ottillia “Toots” Bier, UCR)

navel split

Lemons, Citrus, Spain, EU and Forecasts

According to the latest USDA Foreign Agricultural Service GAIN Report (Global Agricultural Information Network), the European Union is still a major citrus producing area. EU citrus production is concentrated in the Mediterranean region. Spain and Italy represent the leading EU citrus producers, followed by Greece, Portugal, and Cyprus. For MY (October/September) 2018/19, Post expects overall citrus production to grow mainly in Spain due to favorable weather conditions. The quality of the fruit is forecast to be excellent and EU domestic consumption of citrus may stay flat in 2018/19.

EU lemon production is forecast to grow 10 percent and is stable compared with previous estimates. The overall growth is due to the strong production rise expected in Spain, the largest lemon EU producer. According to the latest data from the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food (MAPA), Spain's 2018/19 lemon production is forecast at 1.1 million MT, an increase of 19 percent compared to the previous year. Favorable weather conditions resulted in good flowering and fruit setting. In addition, in recent years Spain has increased its total planted area for lemons. Fruit quality is forecast to be excellent. ‘Fino' lemon is expected to increase by 14 percent due to the entry of new plantations over the last years. ‘Verna' lemon is expected to rebound; increasing by 90 percent as production of ‘Verna' lemon in the previous season was shorter than normal levels. Spain will continue to consolidate its leading commercial position in Europe with quality and phytosanitary guarantees. Following Argentina, Spain is the second largest lemon producer in the world but the first global exporter of lemons for fresh consumption. Spanish lemon production is concentrated in the regions of Murcia and Valencia, and the Provinces of Malaga and Almeria in Andalusia. ‘Fino' and ‘Verna' are the leading lemon varieties grown in Spain, accounting for 70 and 30 percent of the total production, respectively. The ‘Fino' variety is predominantly used for processing.

So far, Asian Citrus Psyllid and HLB are not a problem in the lemon producing areas of Spain and Italy. Read more about the citrus industry in the European Union – oranges, grapefruit, mandarins, fresh, processed, policy, export issues, MRLs and tariffs. Fascinating stuff and the potential impacts it has on California growers and production.

And what about what's going on in the Moroccan citrus world, right next door to Spain?

lemon spanish nipples

A Mandarin is NOT an Orange and Shouldn't be Treated as One

One of the major challenges facing citrus integrated pest management (IPM) in California is the recent, sharp increase in the acreage of mandarins being planted. The current citrus IPM guidelines have been established from years of experiments and experience in oranges, with no specific guidelines for mandarins. In the absence of research into key arthropod pest effects in mandarins, the assumption that the pest management practices for oranges appropriately transfer for optimal production in mandarins has not been tested. We used a data mining or ‘ecoinformatics' approach in which we compiled and analyzed production records collected by growers and pest control advisors to gain an overview of direct pest densities and their relationships with fruit damage for 202 commercial groves, each surveyed for 1–10 yr in the main production region of California. Pest densities were different among four commonly grown species of citrus marketed as mandarins (Citrus reticulata, C. clementina, C. unshiu, and C. tangelo) compared with the standard Citrus sinensis sweet oranges, for fork-tailed bush katydids (Scudderia furcata Brunner von Wattenwyl [Orthoptera: Tettigoniidae]), and citrus thrips (Scirtothrips citri Moulton [Thysanoptera: Thripidae]). Citrus reticulata had notably low levels of fruit damage, suggesting they have natural resistance to direct pests, especially fork-tailed bush katydids. These results suggest that mandarin-specific research and recommendations would improve citrus IPM. More broadly, this is an example of how an ecoinformatics approach can serve as a complement to traditional experimental methods to raise new and unexpected hypotheses that expand our understanding of agricultural systems.

Read on:

citrus manual