Posts Tagged: plants

Cruel Vine

So I've gotten a few calls lately about this vine with a big green pod that is growing in lemon trees. What is done with it and how do you get rid of it?

Araujia sericifera, cruel vine, moth plant, bladderflower is an escaped ornamental that has become an invasive weed in California. Yes, a pretty vine brought into the garden – “poor man's stephanotis” - and it's gotten out of the garden into southern California. It's in the hills, in abandoned orchards, on backyard fences and when it gets into a lemon tree, it takes some effort to remove it before the seeds spread to other trees and beyond.

Bladderflower is a perennial vine that is very vigorous where it gets summer water. It is a common weed in citrus groves, where it would enshroud & smother entire trees if not controlled. Stems are tough and ropy, leaves thick & slightly spongy. Sap is milky white, moderately poisonous & causes skin irritation. It flowers Aug-Oct and the seed pods are obvious later in the fall. The flowers have a pleasant fragrance like jasmine. The reason for gardeners planting it. Plus it grows fast in our environment.

The plump pods produce copious seeds when ripe. The fruit splits down one side and turns itself inside out. The numerous, loosely attached seeds parachute away on silky hairs, dispersed by the wind – on to the next tree or fence.

So the vine is entrained in the tree canopy so you cant spray an herbicide. To get rid of it, it's important to get down to the base of the tree and cut it out at ground level, removing as much of the root as possible. It still can regenerate, so it will be necessary to monitor the site, removing new growth as it might happen. Be sure to use hand protection because many people are allergic to the sap. Just cutting the vine at its base is sufficient to kill it. Removing the rest of the vine is necessary if there are pods, in order to prevent them going to seed.

The upside of the plant aside from the fragrant flowers is that it is an alternative food source for monarch butterfly caterpillars.

Calfflora shows cruel vine spread mostly along the coast south of San Luis Obispo, but it has the potential to spread thoguhout much of California. Currently, in the US, it is only found in California and Georgia. It is in New Zealand and Australia.

Calflora Description and Distribution of Bladderflower

USDA Description of Plant as attachment below:

Araujia sericifera WRA

Deconstructing Plant and Soil Myths

Washington State University and UCCE - Ventura County, respectively

Horticultural myths, found extensively in print and online resources, are passed along by uninformed gardeners, nursery staff, and landscape professionals. Occasionally myths are so compelling that they make their way into Extension publications, used by Master Gardeners as educational resources. In this article we deconstruct seven widespread gardening myths by way of reviewing research-based literature. We also provide scientifically sound alternatives to these gardening practices and products. Our hope is to arm Extension educators with the educational resources necessary to battle misinformation that ranges from the merely useless to that which is actively damaging to soils, plants, and the surrounding environment.

Home gardeners and landscape professionals are a rapidly growing audience for extension educators as they seek science-based information to support their activities. However, many are not familiar with current research and cannot assess whether the information they find in print, on the internet, or through social media is accurate. In addition, some products and practices are meant for agricultural production, not for maintaining home gardens and landscapes. The combination of misinformation and misapplied information means that this audience risks damaging their plants and soils through overuse of fertilizers, misuse of pesticides, and poor management practices.

The field of urban horticulture, including arboriculture, is expanding with new insights about plants and soils in residential and public landscapes. However, there are few Extension educators who have an academic background in environmental horticulture and may be as confused as the public about what constitutes sound, science-based recommendations.

The authors of this article are state Cooperative Extension educators and researchers with many years of experience in translating science for use by home gardeners and landscape professionals. Our goal is to assist other Extension educators by providing reliable information for them to share with the gardening and landscaping public.

The purposes of this literature review article are:

- to identify some common beliefs homeowners and landscape professionals have about managing landscape plants and soils;

- to provide a brief, science-based explanation on why these beliefs are not accurate;

- to provide links to published, peer-reviewed information that supports the explanation and can be distributed to clientele; and

- to suggest strategies based on current and relevant applied plant and soil sciences for managed landscapes.

And here is the article:

Garden Myth Busting for Extension Educators: Reviewing the literture on Landscape Trees

https://www.nacaa.com/journal/index.php?jid=885

roots shallow

Start Poking Around and See What You Will Find in Your Orchard

A recent request from the San Diego area has prompted the reposting of this blog by Guy Kyser, UC Davis Plant Sciences Specialist

//ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=6296

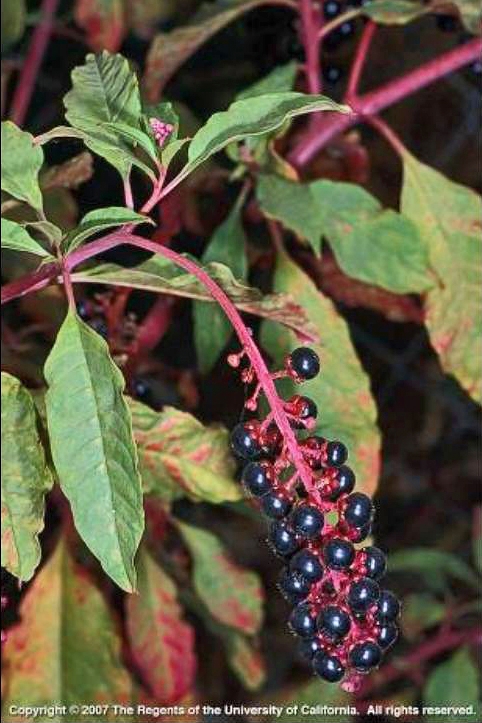

A neighbor asked me to identify a robust perennial that keeps coming up in his garden. It had long, tropical-looking leaves and floppy racemes with small white flowers. This was a new one for me. Turned out it was common pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), a native of eastern North America. In the south some people eat it (poke salad), and a few southerners probably brought it west as a garden vegetable. But the whole plant is toxic if improperly prepared, so it's the fugu of weeds.

A couple of weeks later my daughter brought home a stalk of purple berries and asked if she could eat them. “No,” I said, “they contain numerous saponins and oxalates.” I began to wonder if there's more pokeweed around than I realized.

Then Gillies Robertson of Yolo RCD sent photos of a purple-berried plant found along a slough near Grimes. Common pokeweed again.

Pokeweed is in the Phytolaccaceae. This weed can grow to 10 feet tall. It dies back in winter then reemerges from the ground in spring, growing from a fat fleshy storage root. The leaves are large, 3 inches to a foot long and 1 to 5 inches wide, often with reddish stalks and lower veins. From August to October, pokeweed produces racemes of white flowers followed by reddish-purple berries. In its natural state, all parts of the plant, especially the root, are toxic to humans. Birds can eat the berries but sometimes act funny afterwards.

This plant can be found in most of the contiguous states. In drier regions, it prefers gardens and irrigated areas. Southerners with pokeweed experience suggest controlling it by digging up as much of the taproot as possible and/or by cutting off the stalks and painting the stubs with concentrated glyphosate (e.g. Roundup). Either way, treatments will probably have to be repeated until the plant's storage reserves are worn down. And it's a good idea to deal with pokeweed before it produces berries and seeds.

Since this is the first year I've seen it, and since I suddenly ran into it in three locations within a few weeks, I'm guessing that the common pokeweed population is expanding. This plant seems robust enough to cause some trouble if it becomes established in natural riparian areas.

pokeweed 2

Stinknet Is a Weed?

This is a Wilen repost: //ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=27499

I recently attended a Santa Ana River - Orange County Weed Management Area (SAROCWMA) meeting and there was the opportunity for participants to update the group about new invasive plants as well as give an update on management of these and others. During the discussion, Ron Vanderhoff from the Orange County Native Plant Society (OC-CNPS), reported on new findings of a plant I never heard of. In fact, when they group was talking about it, I wasn't sure if I heard the name right.

The plant is called stinknet (Oncosiphon piluliferum), which to me sounds like a game played by 10 year olds. However, the OC-CNPS considers it an emerging invasive weed (http://www.occnps.org/PDF/HYS-Oncosiphon-piluliferum.pdf). On the California Invasive Plant Council's weedmapper, it was first reported in the Orange Co. in 2003 but was in San Diego Co. as early as 1998 and Riverside Co. in 1981. According to the USDA-NRCS plants database, it has a limited distribution in the U.S., being found only in Orange, Riverside, and San Diego Counties in California and Maricopa, Pinal, and Yavapai Counties in Arizona. However, Cal-Flora has unconfirmed sightings of it in San Bernardino, Imperial, and Kern Counties.

Stinknet or globe chamomile is a relatively small annual plant that could easily be confused with the turf and landscape weed pineappleweed http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/WEEDS/pineapple_weed.html until you smell it. Pineappleweed flowers have a pleasant sweet smell while, as you may guess from the name, stinknet has the opposite odor. It is most noticeable when flowering (March to July in S. California) so now is a good time to spot it.

All photos by and courtesy of Ron Vanderhoff

Although it is not listed as noxious weed, land managers should still be on the lookout for it especially in along the coast and inland. It can be particularly damaging to in coastal sage scrub where because of its tendency to fill in open spaces, it can reduce growth of other native annuals and impact animals that depend on the openings in these areas.

P.S. Stinkweed should be susceptible to standard weed management practices. Ben

stinknet weed

Insectary Plantings, Think About Them.

Home is where the habitat is: This Earth Day, consider installing insectary plants

—Stephanie Parreira, UC Statewide IPM Program

Help the environment this Earth Day, which falls on Sunday April 22 this year, by installing insectary plants! These plants attract natural enemies such as lady beetles, lacewings, and parasitic wasps. Natural enemies provide biological pest control and can reduce the need for insecticides. Visit the new UC IPM Insectary Plants webpage to learn how to use these plants to your advantage.

The buzz about insectary plants

Biological control, or the use of natural enemies to reduce pests, is an important component of integrated pest management. Fields and orchards may miss out on this control if they do not offer sufficient habitat for natural enemies to thrive. Insectary plants (or insectaries) can change that—they feed and shelter these important insects and make the environment more favorable to them. For instance, sweet alyssum planted near lettuce fields encourages syrphid flies to lay their eggs on crops. More syrphid eggs means more syrphid larvae eating aphids, and perhaps a reduced need for insecticides. Similarly, planting cover crops like buckwheat within vineyards can attract predatory insects, spiders, and parasitic wasps, ultimately keeping leafhoppers and thrips under control.

Flowering insectaries also provide food for bees and other pollinators. There are both greater numbers and more kinds of native bees in fields with an insectary consisting of a row of native shrubs planted along the field edge (called a hedgerow). Native bees also stay in fields with these shrubs longer than they do in fields without them. Therefore, not only do insectaries attract natural enemies, but they can also boost crop pollination and help keep bees healthy.

Insectary plants may attract more pests to your crops, but the benefit is greater than the risk

The possibility of creating more pest problems has been a concern when it comes to installing insectaries. Current research shows that mature hedgerows, in particular, bring more benefits than risks. Hedgerows attract far more natural enemies than insect pests. And despite the fact that birds, rabbits, and mice find refuge in hedgerows, the presence of hedgerows neither increases animal pest problems in the field, nor crop contamination by animal-vectored pathogens. Hedgerow insectaries both benefit wildlife and help to control pests.

How can I install insectary plants?

Visit the Insectary Plants webpage to learn how to establish and manage insectary plants, and determine which types of insectaries may suit your needs and situation. If you need financial assistance to establish insectaries on your farm, consider applying for Conservation Action Plan funds from the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) offered by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Sources:

- Flower flies (Syrphidae) and other biological control agents for aphids in vegetable crops. (PDF)

- Good news for hedgerows: no effects on food safety in the field.

- Hedgerow benefits align with food production and sustainability goals.

- Habitat restoration promotes pollinator persistence and colonization in intensively managed agriculture. (PDF)

- Reducing the abundance of leafhoppers and thrips in a northern California organic vineyard through maintenance of full season floral diversity with summer cover crops.

insectary plants