Posts Tagged: Steve Quarles

Can homes be designed to withstand wildfire?

[This story was originally published Oct. 4, 2021, and updated Dec. 21, 2022]

In 2018, the Camp Fire destroyed nearly 19,000 structures in Northern California, including most of the town of Paradise. The structures left standing by the conflagration provided researchers an opportunity to investigate how housing arrangement – such as the size of the lot, the distance to a neighboring home, and surrounding vegetation – influenced which homes survived. They also looked at whether changes to the California Building Code in 2008, through the addition of Chapter 7A, improved the chances of homes built in the wildland-urban interface to withstand wildfire.

Both housing arrangement and surrounding vegetation likely influenced the survival of homes during an extreme wildfire, according to new research from the USDA Forest Service and the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources analyzing the Camp Fire aftermath, which will be published Oct. 3 in the journal Fire Ecology.

“Our team found a reason for hope and information that can help Californians, building contractors and policymakers better prepare for future fires,” said co-author Yana Valachovic, University of California Cooperative Extension forest advisor.

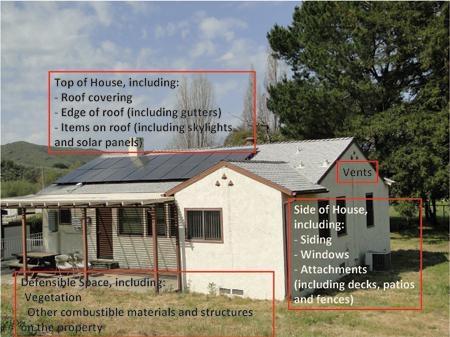

The 2008 code, which applied to the city of Paradise, requires the installation of vents that resist flames and embers and other elements that help harden a home to wildfire. This chapter of the California Building Code added requirements for construction materials to California's existing two-zone fuel and vegetation modification guidance, known as “defensible space,” which applies to the vegetation and fuels out to 100 feet from a home.

The researchers found that the age of the home was a significant factor in predicting survival. But the key year wasn't 2008. Improvements in performance happened earlier. Only 11% of single-family homes built in or before 1996 survived, compared with 40% for homes built after 1996. Older homes were, on average, placed closer together and had more overstory tree growth near the home. Overall, the greater the distance between structures, the lower the likelihood of a home being destroyed by the Camp Fire. And the less overstory tree canopy cover, the higher the likelihood of a home surviving.

During a wildfire, structures can be threatened by the flaming front of the fire and by embers that are lofted ahead of the fire and land on fuels such as vegetation or mulch next to the house, igniting new fires. Embers can also enter homes through open windows or vents. Heat radiating from adjacent burning buildings or vegetation can also impact home survival.

In 2022, during a visit to Laguna Niguel after the Coastal Fire, Valachovic saw that defensible space had prevented flames from reaching homes. However, some houses had burned from the inside out after embers penetrated attic vents and ignited combustible materials.

“Despite the unpredictable nature of wildfire, strong associations with home arrangement and overstory vegetation cover indicate home survival is at least somewhat predictable,” said lead author Eric Knapp of the USDA Forest Service. “The silver lining is that this also suggests steps can be taken to substantially improve the odds of homes surviving a wildfire.”

One of the biggest drivers of home loss in the Camp Fire was the heat radiating from the large number of structures that burned. Over 73% of homes destroyed in Paradise had a structure burn within 59 feet. The distance to the nearest destroyed structure or total number of destroyed structures within 328 feet was a primary predictor of home loss.

“Exposure to the heat of a nearby burning structure can break glass in a window, for example. Once the glass is broken, embers or flames can enter the house,” said co-author Steve Quarles, emeritus UC Cooperative Extension advisor and retired chief scientist for the Insurance Institute for Building & Home Safety.

This finding suggests that denser developments, built to the highest standards, may protect subdivisions against radiant heat from a vegetation fire, but density may become a detriment once buildings ignite and radiant heat loads increase as well as the increased potential for direct flame contact.

“This research suggests a strong neighborhood effect, where the condition and proximity of an outbuilding or a neighbor's home can have a significant influence on a building's survival given the radiant heat exposure from a neighboring building burning,” Valachovic said.

Tree canopy cover was also associated with home loss, with a higher probability of home survival where tree cover was moderate or less.

“Trees provide shade, which is important where summers are hot. But to have the amenities trees provide without undue fire hazard, the key is to clean up the leaves and dead wood trees produce,” said Knapp. “This includes keeping roofs, gutters, garden beds adjacent to the structure and spaces under attached decks, free of leaves.”

The researchers detected no significant increase in survival for homes built from 2008 to 2018, under the new building code, compared to homes constructed during an equal time period, 1997 to 2007, immediately preceding the adoption of the new code. Houses built during the last two decades resisted wildfire better than older homes, indicating an overall improvement in common construction standards and the performance of building materials.

“It is important for Californians to understand that homes and immediate surroundings need to be well-maintained to resist embers, survive extended radiant heat exposures and minimize direct flame contact,” Quarles said. “Fortunately, all building codes get better with time and Chapter 7A is no exception – Californians have benefited from it. California's Building Code is reviewed every three years, and it is evolving as new knowledge becomes available based on research and post-fire assessments.”

To enhance wildfire protection at the neighborhood scale, the researchers recommend coordinating efforts with neighbors.

“Because ember ignition of one house can put neighboring houses at risk, it is critical that fuel reduction happens at a community scale. Living with fire means doing all things possible to prevent one's house from catching fire,” said Valachovic.

There are simple actions that homeowners can take to protect their homes.

“From retrofitting with vents that resist ember entry or using tempered glass windows, to the simple things, like not placing bark mulch or woody plants next to homes, and using gutter guards to minimize leaf and needle accumulation in gutters, all will improve the chance of home survival,” Quarles noted. “It is a matter of how we choose to live in this environment.”

“Housing arrangement and vegetation factors associated with single-family home survival in the 2018 Camp Fire, California” by Knapp, Valachovic, Quarles and Nels G. Johnson is published in the journal Fire Ecology at https://fireecology.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42408-021-00117-0.

For more information:

- Steps for hardening houses against wildfire can also be found at the Fire in California website: https://ucanr.edu/sites/fire/Prepare/Building.

- Reducing the vulnerability to buildings to wildfire: vegetation and landscape guidance https://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf/8695.pdf

Landscaping with wildfire exposure in mind can protect homes

What can Californians do to improve the chances that their homes will survive a wildfire? Simple actions taken around the home can substantially improve the odds that a home will survive wildfire, according to UC Cooperative Extension advisors.

During wildfire, structures are threatened not only by the flaming front of the fire, but also by flaming embers that are lofted ahead of the fire front and land on fuels such as vegetation or mulch next to the house, igniting new fires. Traditional defensible space tactics are designed to mitigate threats from the flaming front of the fire but do little to address vulnerabilities to embers on or beside a structure.

“Without attention to ember-related risks, defensible space efforts only address a portion of the wildfire threat—especially during wind-driven fires in which embers are the primary source of fire spread,” said co-author Yana Valachovic, UC Cooperative Extension forest advisor in Humboldt and Del Norte counties.

An updated University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources publication describes how embers, radiant heat, and direct flame contact ignite buildings and shares low-cost actions residents can take to create effective defensible space.

“The new publication is up-to-date with the changes in California's defensible space guidance, and it addresses Zone Zero, or the missing ingredient, in defense space,” Valachovic said. “The publication also provides a thoughtful discussion of plant lists and their limitations.”

The odds of a home surviving a wildfire can be substantially improved through careful attention to three things: careful design and maintenance of landscaping; awareness and management of combustible materials on the property such as leaf litter, wood piles and lawn furniture; and incorporation of fire- and ember-resistant construction materials with appropriate installation and maintenance.

“You don't have to spend a lot to protect your home from these wildfire threats,” said Valachovic.

Zone Zero, the area within five feet of the house, is the most vulnerable area around the home, according to the UC Cooperative Extension researchers. “During wind-driven fires, embers are the primary source of fire spread,” Valachovic said.

They recommend removing combustible plants, planter boxes, mulches and wood piles within the five-foot perimeter of the house and beneath attached decks.

“While it may be a radical change, clearing the area next to the house will reduce the risk of ember-caused direct flame contact and radiant heat exposure, which are responsible for many home losses,” she said. “Because embers can accumulate at the base of an exterior wall, it is also important to create a six-inch noncombustible zone between the ground and the start of the building's siding.”

Colorful illustrations in the publication depict the three-zone defensible space strategy and show how spacing out trees on a sloped landscape can prevent fire from climbing from tree to tree to reach a house at the top of the slope.

The 12-page “Reducing the Vulnerability of Building to Wildfire: Vegetation and Landscaping Guidance” is available free for download at https://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/pdf/8695.pdf.

“Landscaping for fire is part of an overall strategy aimed at reducing risk to the home,” said co-author Steven Swain, UC Cooperative Extension environmental horticulture advisor for Marin and Sonoma counties. “To reduce the risk of home loss, start at the house and work out from there,” he recommended.

Swain, Valachovic and Stephen Quarles, UC Cooperative Extension advisor emeritus, are currently updating a publication on retrofitting houses for wildfire resiliency.

Steps for hardening houses against wildfire can also be found at the Fire in California website: https://ucanr.edu/sites/fire/Prepare/Building.

Wildfire preparedness bill puts UC research to work

Last week, Governor Gavin Newsom signed a series of bills aimed at improving California's wildfire prevention, mitigation and response efforts. AB 38, a bill aimed at reducing wildfire damage to communities, incorporates University of California research to help protect California's existing housing.

“Prior to AB 38, the State's wildfire building policy focus was centered around guiding construction standards for new homes and major remodels,” said Yana Valachovic, UC Cooperative Extension forest advisor for Humboldt and Del Norte counties. “How do we help incentivize homeowners to upgrade and retrofit the 10 million or more existing homes in California to help them become more resilient to wildfire? AB 38 is an attempt to start that important work and to protect Californians.”

AB 38, introduced by Assemblymember Jim Wood (D-Santa Rosa) provides mechanisms to develop best practices for community-wide resilience against wildfires through “home hardening,” defensible space and other measures based on UC ANR research. This bill is especially important to Wood because wildfires in 2017 destroyed lives and hundreds of homes in his district and because of his work as a forensic dentist following the Santa Rosa and Paradise wildfires.

“AB 38 was a huge effort by many partners as we sought the best policy solutions to address what is today one of our state's biggest challenges,” said Assemblymember Wood. “I could not have accomplished it without the support and guidance of the people at UC Cooperative Extension Humboldt-Del Norte, especially Dr. Steve Quarles and Yana Valachovic. Their expertise proved invaluable as we worked through this process.”

Studies conducted by Steve Quarles, emeritus UC Cooperative Extension advisor, and his continued work at the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety have identified building materials and designs that are more resistant to flying embers from wildfires. Embers are small, fiery pieces of plants, trees or buildings that are light enough to be carried on the wind and can rapidly spread wildfire when they blow ahead of the main fire, starting new fires on or in homes.

Evaluating the homes lost in wildfires that ravaged Paradise, Redding and Santa Rosa have also informed Valachovic and Quarles' recommendations.

Hardening a home to withstand wildland fire exposure does not have to be costly, but it does require an understanding of the exposures the home will experience when threatened by a wildfire.

Their recommended best practices for hardening homes against wildfire can be found in UC ANR Publication 8393 “Home Survival in Wildfire-Prone Areas: Building Materials and Design,” which can be downloaded for free. More information is also at the ANR Fire website https://ucanr.edu/fire.

It only takes a spark

The Las Conchas fire that recently consumed nearly 137,000 acres in Los Alamos, N.M., serves as a reminder of how quickly fire can move if given fuel. I can’t light a barbecue with matches and lighter fluid, but a small ember drifting on the wind can find so many ways to burn down people’s homes if given the right conditions.

Removal of vegetation near Los Alamos National Laboratory, which is part of the UC system, created a buffer and helped spare the lab from the Las Conchas fire, which came within 50 feet. Creating a buffer is one of many preventive measures that can be taken to protect property from wildfires.

In a wildfire-prone area, even if you have a house with a concrete tile roof and noncombustible siding, an ember landing on landscape mulch, igniting plants around the home or floating into a vent on the house or under decks may set the house ablaze, warns a UC Cooperative Extension fire expert.

“From years of observing the aftermath of fires and testing fire-resistant building materials, we have developed a much better understanding about what happens,” says Steve Quarles, UC Cooperative Extension wood performance and durability advisor.

Quarles lists six priority areas for evaluating the vulnerability of homes in fire hazard zones: the roof, vents, landscape plants, windows, decking and siding. For details on how you can reduce the threat of wildfire to your home, visit Quarles' Homeowner's Wildfire Mitigation Guide.

“We know that the zone within about five feet of the home is very important to home survival during a wildfire,” Quarles says.

Landscape mulch provides many benefits to a garden, but Quarles and his colleague Ed Smith, University of Nevada Cooperative Extension natural resource specialist, found that many types of mulch are capable of catching fire and burning. Within five feet of a house, they recommend placing only rock, pavers, brick chips or well-irrigated, low-combustible plants such as lawn or flowers.

Quarles and Smith have published a new manual comparing the relative susceptibility of eight mulch treatments to igniting and burning. To download a free copy of “The Combustibility of Landscape Mulches,” visit the UC Fire Center website.

The scientists tested eight types of landscape mulches, shown in this test plot.