Posts Tagged: alcohol

Lemons are the zucchini of winter - take 2

It's early spring, and that means one thing: I am once again drowning in lemons. This year with our tree well established, we had a bumper crop. Even as an espalier, our tree produces more lemons than we can use. And as anyone with a lemon tree knows - it's almost impossible to give away lemons. Lemons are the zucchini of winter.

With a pantry full of marmalade, a batch of salted lemons preserving, and all of the copper gleaming, I was looking for a new way to use my harvest. A neighbor told me she distributed all of her lemons by having a lemoncello making contest with her friends. Lemoncello, the Italian lemon liqueur, is gaining popularity outside of Italy. It uses a lot of lemons and is easy to make.

The basic recipe for lemoncello is the same. Lemon zest, alcohol, simple syrup, and time. While recipes vary little, proportion and procedures are highly guarded secrets of the cognosenti.

Purists insist on using a base of grain alcohol; it imparts no flavor of its own to the lemoncello letting the lemons shine through. Where grain alcohol is unavailable, a high quality vodka can stand in. I chose a hand crafted corn based vodka, distilled 6 times, because corn seemed the closest to grain alcohol and it had a relatively high proof.

For my first try, I am halving the basic recipe. The first step was to zest the lemons. A lot of lemons.

A microplane is a must-have tool as you want pure zest with no pith.

Add the liquor to the lemon zest. Put it a cool, dark place. Wait. 45 days.

See you mid-May for the next step.

P.S. After the original mixing of the lemon zest and the vodka, and on an apéritif roll, we decided to make vin de pêche using the recipe from Chez Panisse Fruit. The large glass jar photographed above was re-purposed for the vin de pêche, and the vodka and the zest were moved into the empty vodka bottle. This is probably a better solution as there is less air surface in the container.

The fine art of spitting: Allowing underage students to taste alcohol

Not until students turn 21 can they taste the wine and beer they make and learn to assess its sensory quality. Learning the characteristics of a wide assortment of good (and not-so-good) wines and beers is an important component of winemaking and brewing. Having to wait until their junior or senior year to learn these skills is a disadvantage for these students.

Legislation (AB 1989) has been proposed by California Assemblyman Wesley Chesbro (D-North Coast) that will allow students, ages 18 to 21, enrolled in winemaking and brewery science programs to taste alcoholic beverages in qualified academic institutions. The students can taste, but not consume — which means they must learn the professional practice of spitting during the tasting process.

Professor Andrew Waterhouse, an enologist in the Department of Viticulture and Enology at UC Davis, notes that tasting is critical to the students' education.

“Winemakers taste wine daily during harvest to quickly make critical decisions as the winemaking is underway,” Waterhouse said. “Our students need to start learning this skill here, with our guidance. And, they also have to get over the embarrassment of spitting — after every taste.”

Chik Brenneman, the UC Davis winemaker, said that the bill, if passed, “will allow students to move on to the sensory program a lot sooner, before they've finished most of their winemaking classes. Earlier sensory training will help them when they go to work in the industry.”

If the legislation passes, it will benefit enology and brewing students at UC Davis, which is the only University of California campus to offer undergraduate degrees in viticulture and enology and in brewing science (an option within the food science major).

While parents of college students may worry that the bill will open the door to widespread drinking, Waterhouse and Brenneman both noted that the focus of the bill is so narrow that its impact will benefit a limited number of students, and that it's unlikely to lead to excessive drinking. They say that the over-21 students routinely spit what they're tasting in a standard industry manner, and that “drinking” in class is not a problem.

With passage of this bill, which is backed by the University of California, the state will join 12 other states that have allowed this educational exemption for students.

Read more:

- California legislative information on AB 1989

- NBC Bay Area: Reality check: Bill calls for underage tasting on college campuses, Feb. 27, 2014

- Bill by Wes Chesbro would allow underage beverage students to sip; PressDemocrat.com, Feb. 28, 2014

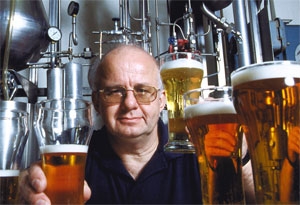

The skinny on beer

Why? Because most of the calories in alcoholic beverages are in the alcohol and wine typically has a higher alcohol content than beer. “The higher the alcohol content in any drink, the more calories it contains,” says Bamforth, the Anheuser-Busch Endowed Professor of Malting and Brewing Sciences.

He contends beer has gotten a bad rap about belly bloating for too long. “For years beer has been blighted by a reputation for being more fattening than other alcoholic drinks when in reality the exact opposite is true," he says. "It really irritates me when I hear the words ‘empty calories’ attached to beer. That's utter nonsense.”

In fact, beer is loaded with stuff that’s good for you. According to Bamforth, there are significant levels of some of the B vitamins in beer — folic acid, for instance — as well as minerals and fiber. “Let me tell you that beer is pretty much the richest source of silica in the diet,” he says. “Detailed studies in the United Kingdom have linked that to bone health. Beer also contains antioxidants such as ferulate.”

And then there's the alcohol itself. The majority of folks worldwide who study the link between moderate alcohol consumption and reduced risk of coronary heart disease are now convinced that the active ingredient is alcohol and not some other component of alcoholic beverages, he adds. So beer is just as effective as wine in this context.

"Now don't get me wrong. I enjoy wine,” Bamforth confides. “But I know that if I want to be genuinely intrigued by an alcoholic drink, then there is much more going on in the world of beer. There’s such a vast array of styles. Something for the depths of winter — perhaps an Imperial stout — to the balmy days of summer — a sparkling lighter lager. All enjoyed in moderation, of course.”

You would expect a professor of brewing sciences to promote ales and lagers as the drink of choice, especially on a hot summer day: “Ya'll better believe me, because beer truly is best.”

Got a question, comment, or request for more information from the beer professor? E-mail him at cwbamforth@ucdavis.edu.

Wine alcohol content is going up

The Wall Street Journal's wine critic, Lettie Teague, said winemakers are beginning to push beyond wine's traditional alcohol-content ceiling of 14 percent - sacrificing the favor of some wine afficionados for flavor and intensity.

The federal government taxes wines with 7 to 14 percent alcohol as "table wine," and taxes wines with 14 to 24 percent alcohol at a much higher rate as "dessert wine."

A wine's alcohol is determined by the grape's sugar content. As grapes ripen, they accumulate sugar, which is converted to alcohol during the fermentation process. The higher the sugar, the higher the potential alcohol of the wine.

UC Davis agricultural economist and director of the Robert Mondavi Institute Center for Wine Economics Julian Alston has charted the sugar content of grapes over the past 30 years, Teague reported. He said grape sugar is on its way up, leading to wine with higher alcohol contents.

Alston attributes the change to climate, later harvests and growing popularity of big-flavored, full-fruit wines.

"Mr. Alston calls this 'the Parker Effect,'" Teague wrote, "a reference to wine critic Robert M. Parker, who seems to get blamed for most things in the wine world these days."

Parker is a U.S. wine critic with international influence, according to Wikipedia. He created a 100-point wine grading system and says he scores wines on how much pleasure they give him. Parker believes corruption and other problems have made his consumer-oriented approach necessary and inevitable.

Meanwhile, many fine wine purveyors won't even try wines with alcohol content above 14 percent, Teague reported."I won't taste wines over 14 percent alcohol, because I want a balanced wine, and I think 14 percent is the threshold of a balanced wine," the story quoted Rajat Parr, wine director of the San Francisco-based Michael Mina restaurant group.

"Is (this) just the next form of wine snobbery . . .?" muses Teague.

Wine tasting (Photo: Brenda Dawson)